For eons, human curiosity has invited us to scrutinize the cosmos, unearthing both fascinating wonders and frightening capacities. Among the latter, one celestial body, stealthy yet potentially catastrophic, emerges as a terror from the skies; the neutron star known as a magnetar. Magnetars and their extreme magnetic fields are an underexplored research area, but of great interest for their potential adverse effects on our planet. This article will examine what Magnetars are, their formation, and what could potentially happen if a Magnetar came close to Earth.

Magnetars and Their Extreme Magnetic Fields

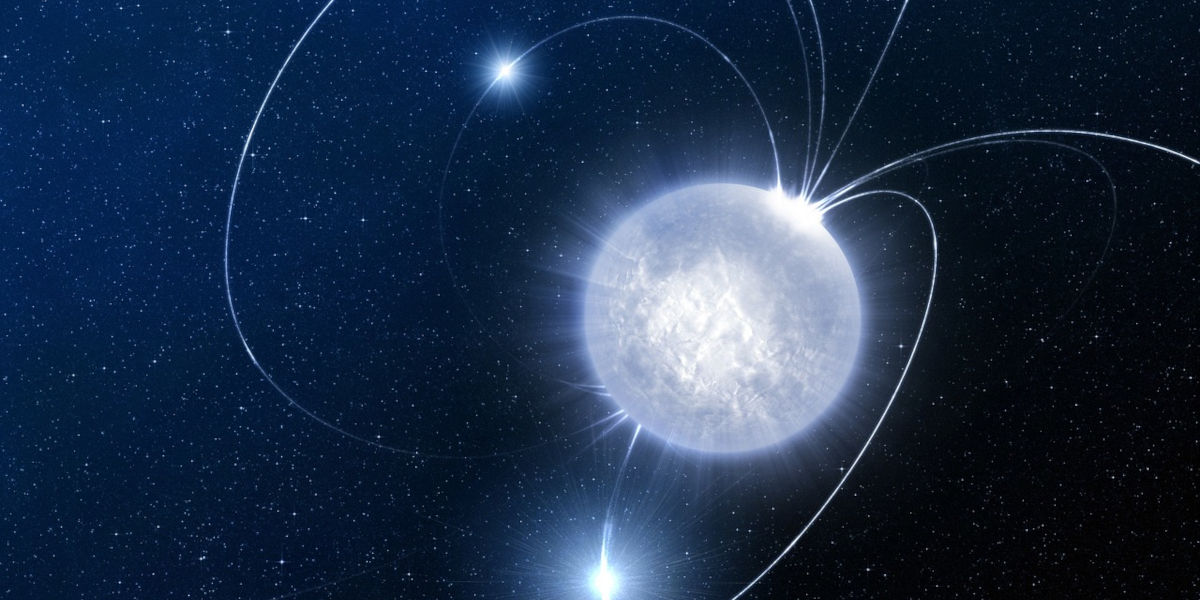

Magnetars are a variant of neutron stars, made from the remnants of massive stars that have exhausted their nuclear fuel, collapsed under their own immense gravity, and exploded as supernovas. However, the singularity of Magnetars lies in their extreme magnetic fields, which are about a thousand times stronger than a typical neutron star's and up to a trillion times more potent than the Earth's.

This mind-boggling magnetic force has the potential to wreak havoc if it comes anywhere near our planet. Due to their strong magnetic fields, Magnetars distort the vacuum of space-time in their vicinity, a bizarre effect uniquely possible in the realms of quantum electrodynamics.According to NASA, there are only about two dozen Magnetars out of the approximately two billion neutron stars in the Milky Way galaxy. Though they are rare to find, a close encounter with one would be dramatically catastrophic.

Magnetar Formation

As with all neutron stars, magnetars form in the violent explosion of a supernova. Nevertheless, the exact mechanism that creates a star's super-strong magnetic field is still a mystery to scientists. Despite this, some astronomy researchers hypothesize that it could involve the star’s rapid spin and the complex dynamics of its molten core. This process, referred to as a dynamo effect, might give birth to these celestial behemoths and their extreme magnetic fields. However, more research is needed before this becomes an accepted theory.

What Would Happen If a Magnetar Came Close to Earth?

Even as we quench our thirst for knowledge about the universe, we should not overlook the potential threats that some celestial bodies might pose. Specifically, a magnetar coming close to Earth would produce catastrophic effects. With a magnetic field believed to be about a thousand trillion times stronger than Earth's, the results would be disastrous. But what specifically would occur?

The intense magnetic field of a magnetar could start affecting the Earth from millions of miles away, forcing particles in the space around the magnetar to perform strange, quantum mechanical gymnastics. Closer still, the magnetic field would be powerful enough to strip away the planet’s protective ozone layer, expose the surface to harmful solar radiation, and potentially even affect the planet's core dynamics. In a nutshell, a magnetar coming near Earth, even if it didn't directly hit us, could spell the end of life on our planet as we know it.

Today, no known magnetar is close enough to pose such an incredible threat. However, the universe is in constant change, and circumstances can evolve. It emphasizes the importance of continued space research and exploration, all while ensuring we apply this knowledge to safeguard our one and only home, Earth.

Understanding Magnetars

Magnetars are neutron stars that are further enhanced by a powerful magnetic field, placing them among the most magnetic objects in the universe. These dense stellar bodies are birthed from collapsing supernovae, an occurrence that leads to a core so heavy that protons and electrons meld together to form neutrons. This event results in the creation of neutron stars. Some of these stars evolve into magnetars – amplified by an incredibly potent magnetic field, approximately a quadrillion times more potent than Earth's.

These fields are not just phenomenally powerful; they are also active. Bursts of X-rays and gamma rays frequently explode from the surface. Additionally, the magnetar's magnetic field strains against the star's solid crust, causing catastrophic starquakes. These starquakes can, in theory, hurl out 'star shrapnel' at a high percentage of the speed of light, causing further destruction.

Explosive Effects of Magnetars

Probably the most infamous magnetar, SGR 1806-20, briefly outshone the whole galaxy in 2004 when it let loose a massive starquake. This event was so energetic that it briefly altered Earth's upper atmosphere, despite being 50,000 light-years away. Should a magnetar be closer, the results could be disastrous.

The Threat to Earth

Should a magnetar form within a few dozen light-years of Earth, the ensuing blasts of energy would be a global cataclysm. The first symptoms would be a bright, blinding flash. Following by a crushing wave of high-energy particles. Communication satellites would likely be the first victims – they're fragile and without the protection of Earth's atmosphere, they would be defenseless against such a strong gamma ray burst.

Our atmosphere and magnetic field would offer some protection for life on the ground, but it's uncertain whether it would be sufficient to counter the full intensity of a nearby magnetar's burst. Simultaneously, some experts suggest that an intense gamma ray burst could start a devastating chain reaction in our atmosphere, spawning chemical reactions that could deplete the ozone layer and create a toxic smog of nitrogen oxides.

Conclusion

Despite the potential threat, the likelihood of a magnetar affecting Earth is astronomically low. This is primarily because of the extreme distances involved. The rare events that we have been able to detect have typically taken place many thousands of light-years away. This does not mean we should be complacent, though. As with many cosmological phenomena, we have much to learn about these stellar titans, not least about how to mitigate their potential impacts. After all, forewarned is forearmed.